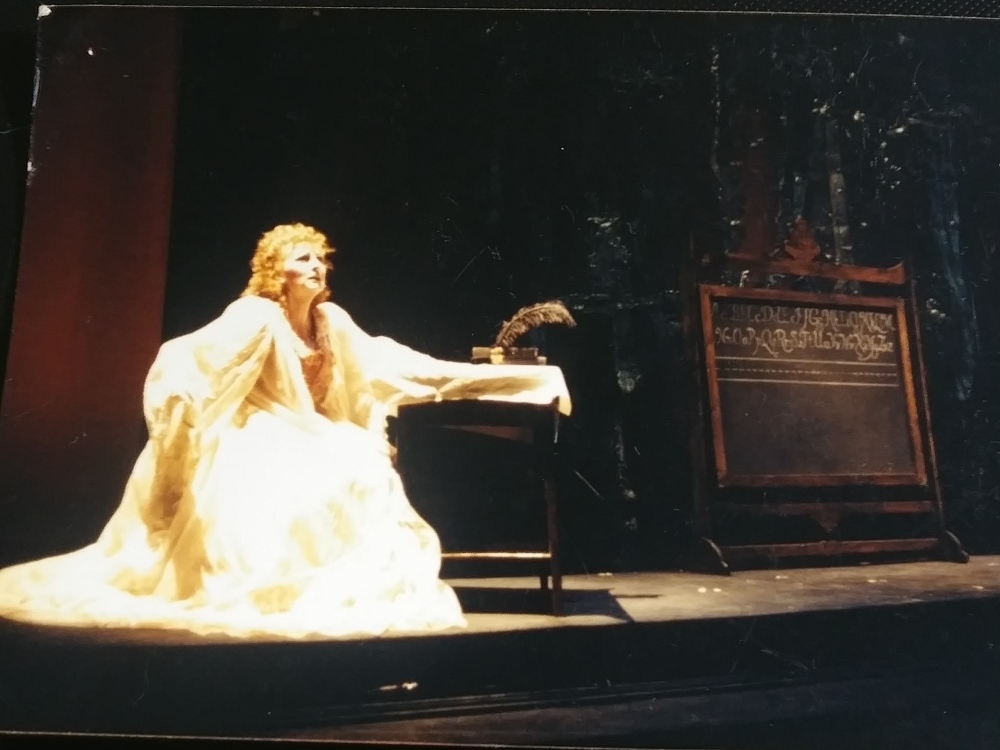

Earlier this week, BPAC Director Ted Altschuler sat down with soprano Lauren Flanigan in the Green Room, to talk about her stunning, career, turning 60, and the World Premiere of Words on the Street, which has its final performances Nov 1 – 4.

Ted: You’ve had an amazing career singing at places like The Met, Glyndebourne, La Scala, and you’re especially known for your work at NYC Opera in its heyday. What is different about performing in an intimate venue like BPAC?

Lauren: I got started early in the 80’s working in out-of-the-way places on the Lower East Side with Anne Bogart, so it was a conscious choice to get back to that, find my roots again. I turned 60 this year, so I’m looking to do something connected with the public in a visceral way.

Ted: You’ve been closely associated with modern and contemporary operas, works by people like Hugo Weisgall and Kurt Weill. What draws you to singing that kind of repertoire?

Lauren: You know it’s funny, I mostly sang Donizetti, Mozart, and Verdi, but the other things got so much attention like Central Park by Deborah Drattell and works by Beeson, the Philip Glass symphony written for me, or Henze’s Venus and Adonis. Those things got so much more attention than so many other things that I did, that I think that the scale tilted in that direction. I was very close with William Bolcom and Arnold Weinstein when they wrote A Wedding for me. I loved those close associations. One of the great motivators that I had as a 20-year-old, was that I wanted to be the kind of artist that creators wanted to work with. In opera that’s unusual because back in the 80s there weren’t a lot of opportunities for living composers. It was largely a career-killer when you would do American works, but I kept going back to the classics, so my voice largely stayed healthy through those years and it allow me to do crazier things like Mourning Becomes Electra, and take bigger risks with my voice, and sing in a much bigger way than I would have in Mozart. It was fun.

Ted: Do you think that’s changed now?

Lauren: Oh my God, it’s completely different. Now if you can’t sing modern opera’s you can’t have a career. You became totally sidelined as kind of a specialist in the ‘80s. In every theater where I made a debut singing a modern opera, I was never asked to sing the classics. City Opera is the only exception because, even though I made my debut as Musetta in La Boheme, the next big piece I did was Esther, and yet they had me back to do Macbeth and Roberto Devereux and Die Tote Stadt. So I got a chance in that theater to do incredible repertoire, but at the Lyric Opera, I was a “modern opera singer.”

Ted: So Words on the Street is a return to your roots as a singer in modern music-theatre?

Lauren: Yeah. It’s definitely a kind of a walk back into working hand in hand with people who have new ideas, want to synthesize different elements and make theater out of all those elements, like video and sound design. I have a neurological disorder and I didn’t know if I would be able to be in an environment that was filled with all these sounds, in the case of Words on the Street, screaming, coughing, and drone sounds. So there was a learning curve in it for me. It’s a real modern construct now that all these elements [go into ] making music, which is really what Matt Marks envisioned, and are now involved in almost every opera.

Ted: How’s the modern voice different now than what we called the modern voice 30 years ago?

Lauren: Well hopefully it’s not different. Hopefully people are able to circumnavigate from Don Giovanni to let’s say, Dog Days by David Little. I think the Metropolitan Opera is banking on the fact that someone as terrific as Isabelle Leonard can move equally between Zerlina in Don Giovanni and modern repertoire with the same beautiful sound and the same approach to classic music making. So I’m hoping it’s the same – it needs to be the same.

Ted: You’ve been doing work lately in the nonprofit sphere as well, you founded the Music and Mentoring House, whose mission is mentoring through an example of leadership musical opportunities, education and community service. So tell us a little bit about that organization.

Lauren: 9 years ago I was diagnosed with sudden senso-neural hearing loss and active Meniere’s Disease. The hair died in my cochlea. Then, the phone literally stopped ringing the next day and I needed something to do. I had been teaching acting to opera singers because I had studied acting my entire career and I thought it would be interesting to have a residence where kids could come (18 and up) who either want my coaching on their repertoire, or they need to use my library, or needed career advice. I found a house to rent and, in the 8 years that we have been doing this, about 240 kids have come through my program. By January 2019, I hope to be certified as a life coach and add that to what I’m able to offer to students.

I invite my friends over, we have this thing called “No Bullshit Mondays,” where famous opera singers come over and have dinner, and I do all the cooking, and they tell the truth. But “what happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas,” so what is said at the table stays private information. They talk about what it’s like to be a married couple and be on the road, or why a woman shouldn’t listen to the popular opinion that if you’re a performer you can’t be married or have a child. We talk about a lot of nitty-gritty things. A really great friend of mine talked about sexual harassment in the workplace. He absolutely laid it out. He said, this absolutely happens, you need to have an eye out for this. I’m trying to find things that are real, that they can take away and use the next day.

Ted: The kinds of things they don’t get in grad school.

Lauren: Right, I’m really trying to fill in that space for them. It’s basically a very very affordable residency program and I’m there, which is good and bad for me personally (laughs) because you know, I can’t get a cup of coffee without someone wanting me to talk about their auditions. It’s a terrific place that I love very much. Right now I live in the oldest house in Harlem on East 128th street. It’s a 156-year-old wooden house with a slate roof. It’s a very beautiful residence. Currently, I have a full-time student who’s in the School for American Ballet and my colleague Sumayya Ali, who’s in Words on the Street, in residence. It’s become a place for performers of all disciplines to gather when they need advice and information, and it’s really what I wanted.

Ted: It’s Monday, what’s for dinner?

Lauren: Well, everyone is on their own this week because I’m “on the clock” now as a performer. That’s kind of an interesting tie-in (I’m on the clock), because I turned 60 this year, and I thought “ok, I don’t want young artists to think that there is this finite period of time that you’re a singer/performer.” I’m also a person with a disability fighting/creating my way back to performing. I want these amazing young performers to create their way into art and music with no end in sight whatever life throws at them. I am firmly attached to this idea of small theater, affordable theater, affordable operas, smaller, intimate ideas, intimate connections, and so that’s where I’m going with this.

Ted: I believe this is your first fully staged production in about 7 years, is that true?

Lauren: In New York. I did Mourning Becomes Electra in 2013 with Florida Grand Opera. Marvin David Levy called and asked me. He knew I had an issue that involved my ability to match pitch, and I have permanent vertigo. The stage largely makes sense to me, but everything that happens in any given show is built into my performance. If a lighting instrument makes noise, for instance, because a fan is cooling it off, that’s built into my performance. I notice that and say it to myself so that it’s not a sound that takes me by surprise. Several years later I did a production of Tosca in El Paso, Texas for a dear friend. I was wondering if that was a role I would like….this is the first time I’ve done any public performances in NYC beyond a Macbeth aria for New York City Opera before it closed its doors.

Ted: What’s it feel like to be returning to New York?

Lauren: Well this is baby steps. Matt [Matthew Marks, composer] was [a] wonderful, quirky, geniusy guy and we [met] because we were both posting golden doodle pictures on Instagram. Anna Rabinowitz, who is the writer of this project, and I have known each other for years. She’s a very serious, deep thinking, poet who loves language. I believe it was her idea to ask me to play Superbia. I was compelled to try it. I adore Kristen Marting [director]. She is a very special human, and there were just so many elements to this project that I thought might really work out well for me. Kristin was very open to understanding my disability and how she could be helpful in the process. Basically, I have to know what sounds I’m going to be hearing, and then build those sounds into my performance. Then I’m on my feet and I don’t fall over (laughs) which is always good.

Ted: I wouldn’t know you had a disability without hearing about it.

Lauren: It’s pretty obvious off-stage. 40 years on my feet onstage I have some kind of wonderful instinct for how that goes. There is nothing that’s left to chance, though, now. There is no improvisatory idea because I really am thinking “here come the coin drops, and you go stage right, and now he says this, and there’s gunfire.” That’s literally what’s going through my head the whole time in the show.

Ted: Do you think about pitch?

Lauren: No. I can’t think about pitch. For a long time, I was trying to vocalize sharp by using a pitch monitor like the kind that the oboe players use to tune the orchestra but I just found it maddening to be glued to a needle on a machine that didn’t take vibrato into consideration. I went to the great soprano, Diana Soviero and I said “I have this problem” and she said, “we’ll figure it out.” So she started showing me a reliable series of exercises that allowed me to really feel the vibrations in the front of my face. I rely on the musical director to tell me that it’s absolutely what they want, and then I just memorize what that is and keep it going.

Ted: Less improvisation on stage and more in life?

Lauren: Well in opera you don’t really improvise, but the more you sing, the larger the spaces feel between the notes. For instance in bel canto, that’s what starts to give you the freedom to do wonderfully crazy things. There’s also that slight freedom between you and the conductor to hold something longer, or do a crescendo, or come off of it a little bit later than usual. In classical music the amount of what you would call improvisation is infinitesimal, it’s almost immeasurable, but it feels huge to us because we’re so measured …largely I’m sticking to the script. I do some crazy dancing in this show (laughs)

Ted: Yeah, I had no idea you could tap dance.

Lauren: Nobody did (laughing). Every time we got to this vaudeville number in the middle of our show, I kept thinking what did she do – Pride [Lauren’s character]- what’s in her arsenal of things that she had in her life? I had been using this through-line that Pride had a baby that died and that Pride’s whole reason for existing now was to corrupt anything that was new and innocent. I was working hard on that, because there is a baby in the show, and then one day we were doing a run-thru and I thought “oh no, this is Toddlers and Tiaras!” Pride is stuck in a time when all of the attention was focused on her and she has never evolved beyond that moment of greatness. The inability to evolve is destructive. And I thought that’s what the posing is all about, the vaudeville. Former greatness.

Ted: All the characters in the Opera are the seven deadly sins.

Lauren: Yes we are all the sins. Lust is the only sin that needs people, and Pride is the only sin that has a good side. Pride in ones, work, education, or singing voice, but Pride once taken to an extreme is like being this child superstar, but then having it stolen away and being locked in this moment, so you’re stuck in time. That’s why we have these tap steps and these routines that were familiar to you as a child. I’ve gone in the direction of that idea.

Ted: Do you have a favorite sin?

Lauren: In our show, I love all of the sins equally (laughs). It’s been interesting to live inside the sins in this way where we’re taking them outside of the parable that Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill set up. We’re imagining them in a 21st century context. It’s given me a lot to think about in terms of anger. Caitlin (Anger in Words on the Street) is a gorgeous 20-year-old, and yet that voice can really bring out a side of anger.

Ted: So your current project is in a dialogue with Weill’s Seven Deadly Sins, which was another role of yours at City Opera.

Lauren: Yes. That’s really interesting. In 1997 we did it with Anne Bogart’s SITI Company, and we knew we were not going to take this typical line through it, that Anna I is only dancing and Anna II only singing. We wanted to explore what it meant for two girls to set out in the world with limited information. I think about that a lot these days. I have young women and young men who come into my house and have had these life experiences and questions and so, I think about this every day. Envy comes up a lot when you’re coaching young people who want what everyone else has. Who have worked really hard at their craft and are not succeeding at a pace they see posted by others to social media. Especially in this world, where it’s all about beautiful posts on Instagram and Snapchat. What do those things really mean? The thing that really sat with me in the context of Words on the Street, was the issue of anger and how is anger expressed, and why is it expressed – when is it appropriate to express, it and why is it hard for us to handle other people’s anger?

Ted: It’s socially forbidden.

Lauren: Yeah, raise your voice and it’s too much for people… it’s been fascinating to look at this and recontextualize it. Anna wrote (Words on the Street) before the 2016 election. She says that she had been grappling with the seven deadly sins for years in the context of how society was evolving, as she saw this turn away from morality. Have we forgotten about them?

Ted: We just talked about what people might find important in Words on the Street. What might they find fun about it?

Lauren: There is humor in it. Matt’s ideal, which I think was so beautifully expressed in an interview with Mary Kouyoumdjian, was that he was very interested in how tuneful music could deliver a serious message. How you could get audiences to hum along with you and they were really humming something that was subversive or that was evil. There is humor in that!

For more information about Words on the Street or to purchase tickets, click here.